I recently read another novel based on a true story that happened during World War II. I say “another” novel, because this is an era of historical fiction that I’m drawn to over and over again. I think the primary reason is because as much as I don’t want to imagine a world in which such terrible things take place, these terrible things take place. They take place everywhere, and reading historical fiction in particular helps make the news and atrocities more than ink and headlines. They take the experiences of thousands upon thousands of people and zoom in on one man. One woman. One human being. That closer lens puts flesh on historical events, an incarnation, so to speak.

I read historical fiction like this to remember history, to put legs on (re-member) facts and figures, dates and dots on a map. Those who record history help us to understand two truths: nothing new happens under the sun, and this doesn’t have to happen again.

Salt of the Earth

“We humans are terrible animals. Extremely violent.”

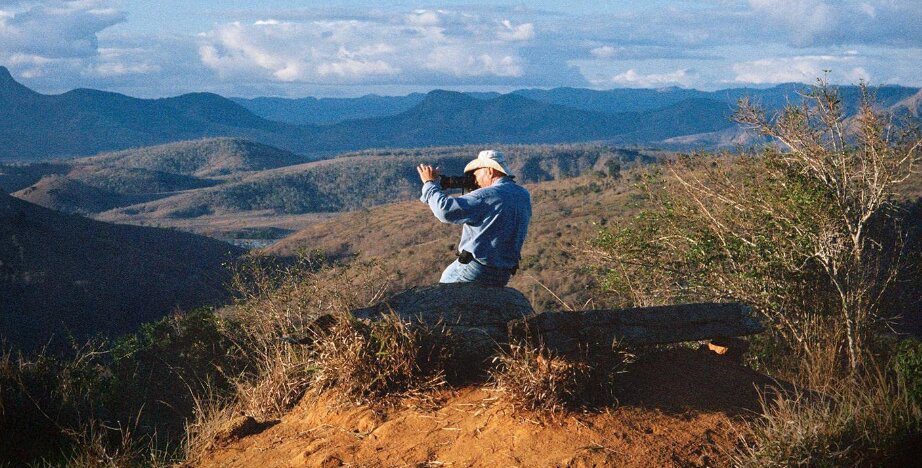

The film Salt of the Earth is a documentary about the life and work of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, who spent his career as a photographer traveling the world, capturing the human experience in all of its tragic grit.

“Our history is a history of wars.”

Salgado grew up on a beautiful farm in the Brazilian rainforest. During political unrest in his early adult years, Salgado was forced to flee his homeland with his wife, leaving Brazil for over a decade. During those years, Salgado—an economist by training—turned away from his formal education and invested everything he had into photography.

“Everybody should see these images to see how terrible our species is.”

After years of capturing the plight of humans around the globe, Salgado returned to his homeland depleted, depressed, and in despair. Years of witnessing human suffering had made his soul sick. His last trip took him into Rwanda and the Congo to document what was happening to the Rwandan refugees who had escaped the genocide in their country.

“When I left there, I no longer believed in anything, in any salvation for the human species. You couldn’t survive such a thing. We didn’t deserve to live. No one deserved to live.”

The homeland Salgado returned to was nothing like the land he remembered. The farm was a wasteland. In his despair, Salgado’s wife made an offhanded remark: Let’s replant the forest that was here.

During the following ten years, they planted two million trees.

“It was a full-blown miracle.” The forest’s restoration healed Salgado’s despair and propelled him back into his calling as a photographer, focusing this time on the untouched lands around the planet. His project, Genesis, is a “love letter to the planet.”

Finding the Love: Faithifying Your Viewing

The Christian story is incomplete without Good Friday. As awful as the events leading up to Jesus’ resurrection were, that death and sacrifice would not have been necessary if it wasn’t for humanity’s fallenness. Remember the mocking voices of the soldiers who beat him? Remember the curses and the taunts? You can almost hear them laughing at Jesus’ suffering.

But this is just one story of human suffering, albeit the greatest Human’s suffering. A history of human suffering preceded Jesus. The Old Testament books of Genesis and Exodus, Joshua and Judges, the Samuels and the Kings, all tell stories about the way humankind has been horrible to each other. They record murders and genocides, rape and incest, drunkenness and rage. God appears on the sidelines, heartbroken and furious, while generations of humans destroy themselves.

The absurdity of all this suffering taken from 40,000 feet is summed up by Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, “Millions of men, renouncing their human feelings and reason, had to go from west to east to slay their fellows, just as some centuries previously hordes of men had come from the east to the west slaying their fellows.”

In the midst of all this suffering, Jesus entered. Jesus, the Light of the world. Jesus, the Son of God. Jesus, the firstborn of the new creation. Forget the old ways, your old truths, your old life, Jesus says; “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life.”

As the firstfruit of the new creation, Jesus opened the seam that separated heaven from earth and let the light shine on a better way.

Two thousand years later, millions of men go from west to east slaying their fellows, and soon, more will come again from east to west to slay their fellows again.

And yet. And yet, and yet, and yet, the gospels promise a new hope. Jesus conquered death. Jesus restores and renews. The answer to the question, “Now how shall we live?” has been answered by Jesus: in love. Live in love.

When you invite the Light of the world into the world, it illuminates the darkness. It stands as a witness to injustice and atrocities. See? See? Look into these eyes, how they suffer. Look into these hearts, how they hurt.

In the documentary, Salgado describes a photographer as “Someone drawing with light, writing and rewriting the world with light and shadows.”

Jesus is the Light. He gives light to his followers, and he calls them the light of the world. Salgado takes on the mantle of light-bearer. He carries his torch into the darkest places so that the blind around the world can see. He carries his torch into the most remote places to show that the ways we have destroyed nature can be reversed. Together with our earth and fellow humans, we can walk out of the tomb we’ve sentenced ourselves to. Christ’s resurrection pointed the way to new life.

Salgado’s life and his life’s work shines with resurrection power.

Copyright

2024

Root and Vine

Copyright

2024

Root and Vine